Book Review of: Laughlin, Robert and Sna Jtz’ibajom. Monkey Business Theater. Austin, TX. University of Texas Press. 2008

Book Review by Carlos D. Torres, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Colorado at Boulder, Dept. of Anthropology

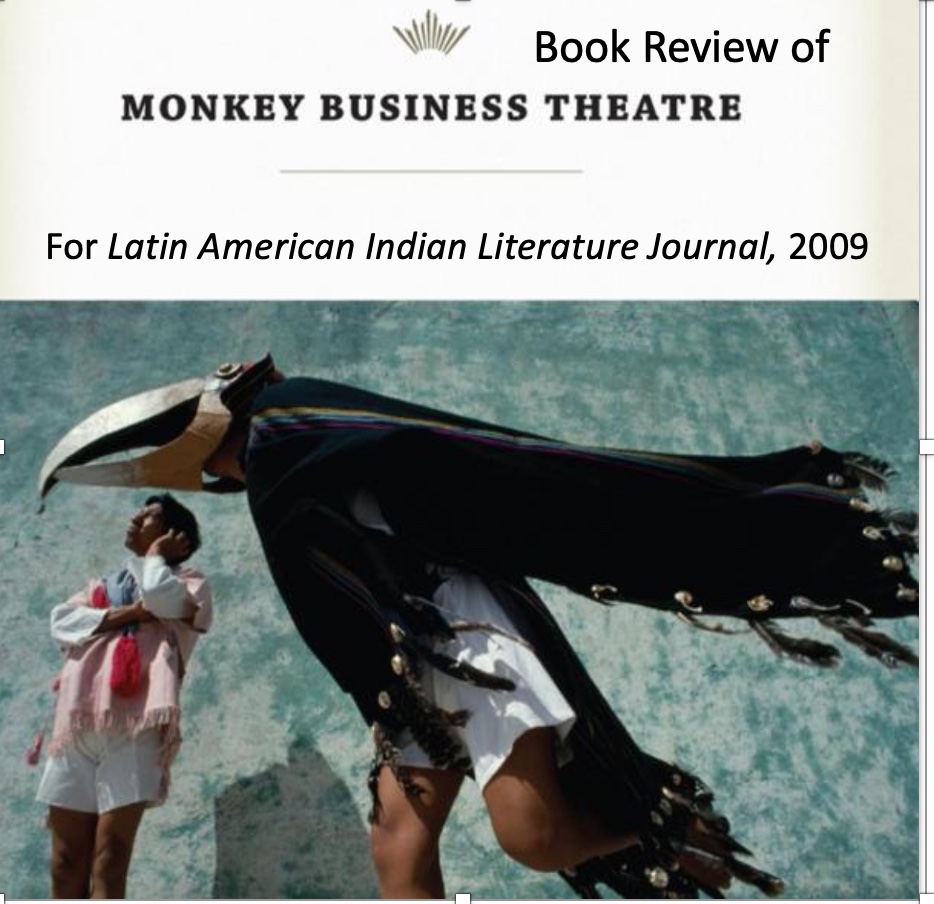

If you visit San Juan Chamula, a large pueblo located in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico, you may see a play being performed at one end of the town square. The playwriting and acting theater group could very well be members of Lo’il Maxil (Loh eel Masheel), Monkey Business Theater. The original plays of this Maya playwriting cooperative are only now becoming available in English translation as a complete dramatic works compendium, Monkey Business Theater (2008, University of Texas Press). The Spanish editions of the plays have long been available at the bookstore of Lo’il Maxil’s parent cultural association, Sna Jtz’ibajom (Sna Htz’ eebajom) located in the cultural heart of highland Maya Mexico, the city of San Cristobal de las Casas. What is unique about this collection, apart from its English translation, is that the first sixty-four pages of the book provide background information about the founding of this grassroots indigenous association, founded with the assistance of anthropologist/linguist Robert Laughlin.

Laughlin was already well established as the foremost chronicler of Maya folklore from the Maya village of Zinacantan, a village which was the focus of anthropologist Evon Z. Vogt’s research for many years. As Laughlin explains, Sna Jtz’ibajom was formed in part by the void left by American researchers by some of the former informants of the Harvard Chiapas Project:

“In 1982 my life took a new turn. I became, to my surprise, an advocacy anthropologist. It happened that I was co-director of a conference in San Cristobal, “Forty Years of Anthropological Research in Chiapas.” Earlier, three ex-members of the Harvard Chiapas Project – Antzelmo; Romin’s son, Xun of Zinacantan; and Maryan Kalixto of Chamula – had asked for my help in creating a Tzotzil-Tzeltal Mayan cultural association. I urged them to speak to the participants of this meeting to plead their cause (Laughlin and Sna Jtz’ibajom 2008:1).”

Sna Jtz’ibajom produced educational bilingual booklets for three years in Spanish and Tzotil/Tzeltal, instituting a six-month Maya language literacy courses, and filling a void that Mexican public education failed to provide (see the play Torches for a New dawn in MBT). Funded in start-up by a $3000 dollar grant from Cultural Survival, a NGO whose goal is to defend indigenous “rights and sustain their cultures,” it was thought that educational booklets might gain readership if Sna Jtz’ibajom added a puppet theater; Maya language education brought out into the public sphere, if you will. The impetus for original playwriting began soon after this realization. The first “puppet” play was penned by Laughlin himself from the Native American/Mayan fable The Loafer and the Buzzard.

Soon after, members of the puppet theater Lo’il Maxil began to write their own plays from drama group members who “learned their lines by heart,” but employed “creative invention…and improvisation” in their mastery of Maya puppet theater (6). They became a Pan-Maya troupe performing in Guatemala in 1987 at the Taller de Linguistica Maya in Antigua, Guatemala, broadening the scope of folkloric topics to include contemporary social issues like “(1) family planning, (2) deforestation and wildlife depredation, (3) racism, (4) indentured labor, and (5) land rights, especially of women” (7). It was during one performance in Guatemala they improvised a live action play from a Chol Maya folktale handed them: “It was the memory of this performance that a year later bolstered the puppeteer’s confidence enough that they considered becoming actors in live theatre” (8).

The plays themselves are a small corpus of an ever-expanding Mesoamerican literary movement that now includes diverse forms of literary and video media, drama, poems, and novels. Monkey Business Theater also becomes one of a few very good recently published anthologies of Mesoamerican literature (See Leon-Portilla and Shorris 2001; Frischmann 2007; Taylor and Constantino 2003). The genres of the plays are often hard to classify in Western terms reflecting deeper Maya considerations of time and place. Mythical/modern or mythical/historical, the bases of many of the dramas are highland Maya village tales, re-combinations of creation “epics,” folk parables, and unique Maya historical retellings. Many of the plays also reflect the current socio-political conditions in Chiapas illuminating Maya sentiment and subjectivity in light of the impact of neoliberal politics, corruption, and traditions of assimilationist state social policies.

“Lessons” in the plays are straightforward, the characters weaknesses transparent. The plots of the plays are illuminating in that they at once inscribe a substantial underlying cultural substrate of enduring Mesoamerican themes, (i.e., sacredness of corn, scorn for arrogance, the value of work) while weaving in contemporary social drama and overlying themes of cultural revitalization . The “moralistic though humorous orientation” of many of the dramas “parallels that of pre-Hispanic morality farces such as “Envy and Spite, which formed part of the Baktun ceremonial held at Merida in 1618” (Frischmann 2007:30). This form of humor is also prevalent in manifestations of “ritual humor observed during the 1960s and 1970s by Victoria Reifler Bricker,” (Frischmann 2007:30) but also commonly observed in the “burlesque-ing” of Spanish colonial figures in contemporary cultural festivals in the Maya villages of Zinacantan, San Juan Chamula, and Tenejapa. The literary themes of the plays are also consistently reinscribed and recomposed in other small media production enclaves in San Cristobal de Las Casas, in photography, Zapatista video production, and in other grassroots writing workshops (Taller Leñateros). These literary themes provide a small but important part of the cultural substrate underlying the “embedded aesthetic” of Maya media production: “a [inner cultural] system of evaluation that refuses a separation of the textual…from broader arenas of social relations” (Ginsburg 1994:368).

Some of the backstory in Monkey Business Theater also reveals some of the process in crafting plays, and the process that goes into converting village tales into modern dramas. Among the best examples of this conversion process comes from the transcription of the play Deadly Inheritance.

“For those who romanticize Mayan culture and, particularly, Mayan family life, this play will be a surprise, for it revolves around one of the most feared elements in the daily life of the people who live in the rural towns… the discord between siblings” (Laughlin and Sna jtz’ibajom 2008:75)

The plot was adapted from a 1987 incident of domestic violence in the Tzeltal township of Tenejapa. Following their parents’ death, two brothers apparently killed the most defiant of their two sisters and hid her body in order to obtain her share of the inheritance (Frischmann 2007:30). The sister’s body was never located, and the suspected assassins were soon released from jail. (30). The writers of Lo’il Maxil decided to drastically alter the plot and the conclusion of the play. In the play as written, the town mayor comes to believe the testimony of the surviving sister and her neighbor and orders the accused brothers arrested. Since the “brothers are already known as troublemakers, and their alibis for the crime are flimsy,” the mayor decides to flog a confession out of them publicly. The weaker brother confesses and the cowardly husband of the witness also finally breaks down and provides testimony. In the end, the mayor sends all three men off to jail, “thus providing the survivors with redress and punishing the guilty” (30). In this way, Deadly Inheritance is shaped by the contemporary moralistic sensibilities of the writers of Sna Jtz’ibajom, reconsidering their own social roles in modern society, reflecting “real life and the desire for justice” (Laughlin and Sna jtz’ibajom 2008:75)

The abiding purpose of the Sna Jtz’ibajom was to create a Maya language literacy program and literary institute. In this endeavor, they have been very successful creating an epicenter for Maya learning, writing, and intellectual output in Chiapas. Inscribing text and literature into books and plays, from stories that only forty years ago were predominantly oral in transmission, Monkey Business Theater has augmented to the rich, ongoing cultural production in Chiapas, adding to a powerful Maya cultural repository that makes clearer the logic behind Maya social activism and self-conscientization. Though the exegesis of the plays is minimal in this anthology, educators (whether political scientists, anthropologists, or comparative literature scholars) will be able to hear Maya voices in Monkey Business Theater, voices that are too often muted by charismatic leaders and non-Maya cultural “proxies.” Reading the commentary by Laughlin and members of Sna Jtz’ibajom (but also taking note of the diverse speech and subject matters in the plays) opens up windows to contemporary Maya sensibilities while bearing witness to cultural recovery in process (Laughlin and Sna Jtz’ibajom:100). The stories of the creation of Lo’il Maxil told in Monkey Business Theater do, in themselves, reiterate a Mayan “enduring value,” a value not uncommon in societies that seek self-empowerment: respect for writing/painting (tz’ib), learning, and derivatively education.

Sources:

Leon-Portilla and Shorris, eds. In the Language of Kings: An Anthology of Mesoamerican

Literature – Pre-Columbian to the Present. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Montemayor and Frischmann, eds. Words of the True Peoples: Anthology of Contemporary

Mexican Indigenous-Language Writers. Vols. 1,2,& 3. Austin, Texas: University of Texas

Press, 2007.

Taylor and Constantino, eds. Holy Terrors: Latin American Women Perform. Durham, North

Carolina: Duke University Press, 2003.